Farmers protest the high cost of fertilisers in Ecuador in July 2021. (Signs read: “Fertiliser and urea more expensive by the day, and our rice cheaper by the day. Rice farmer, speak up! Tremendous abuse! Justice!”) Photo: Ecuavisa

It is hopefully starting to dawn on decision-makers that fertiliser prices are not coming down from their stratospheric heights anytime soon and that this is going to have catastrophic consequences for people’s access to food. More than half the world’s agricultural production, it is said, now relies on nitrogen fertilisers, which are derived from an energy intensive, fossil fuel-based production process. High energy prices and supply issues mean high fertiliser prices – and this translates into decreased food production and higher food prices.

Today, in many parts of the world, farmers are facing fertiliser prices that have skyrocketed, especially since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine triggered a host of supply problems. In many ways, this is a repeat of the 2007/8 food crisis, but the price shocks are more profound this time and the potential consequences even more dire. A timely report from the German civil society organisation INKOTA, which has just been translated to English, shows how the actions of the fertiliser industry are largely to blame.

During the 2007/8 crisis, the companies that dominate global fertiliser production, like other corporations within the food system, used their market power to capture excess profits. INKOTA points to research showing that around half of the price increases during the food crisis of 2007/8 “can be traced back to price agreements and cartel structures between companies”. Flush with cash, the fertiliser companies poured money into consolidating and expanding their power even further. INKOTA shows how they bought up smaller competitors around the world and, just as importantly, deepened their control over the retailing of fertilisers in the global South, often with taxpayer-funded development aid from their home governments.

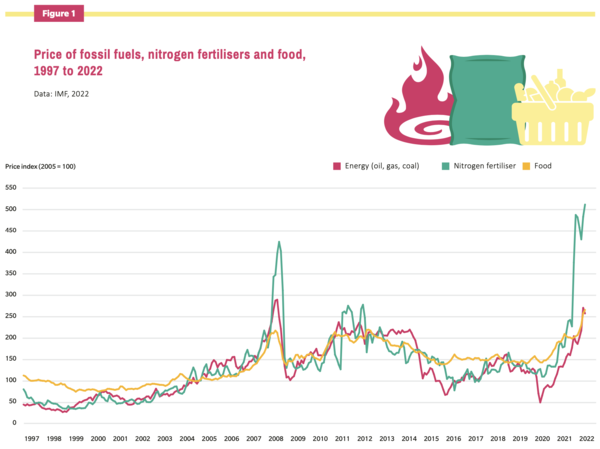

With their increased market power, the world’s top fertiliser companies are able to extract even greater profits from today’s debilitating food and energy crisis. This can be seen in Figure 1 from the INKOTA report, which illustrates how today’s fertiliser price increases are vastly higher than those for energy and food.

Source: INKOTA 2022

Source: INKOTA 2022The high prices reflect, to a large extent, the obscene profits the fertiliser companies are able to take. INKOTA shows how the profits of some of the top fertiliser companies in the first quarter of 2022 have soared compared to the first quarter of 2021. According to our own calculations, the profits for the top three fertiliser companies – Nutrien, Yara and Mosaic – in the first half of this year are higher than their total profits for all of 2021, which themselves were double those of 2020.1 The US$14 billion that these three companies collectively made in profits in the first half of this year is roughly the same size as Africa’s total annual public expenditures on agriculture!

INKOTA calls for price caps and excess profit taxes as emergency measures to try to bring down prices in the short term. But they also emphasise that the crisis cannot be resolved through the production and distribution of more fertilisers. Chemical fertilisers, especially nitrogen fertilisers, are major sources of greenhouse gas emissions and need to be quickly phased-out to combat the climate crisis and the other environmental catastrophes they contribute to. INKOTA calls instead for a ramp up in the production and distribution of organic fertilisers along with extension programmes and support to help farmers implement alternatives, like agroecology.

Africa’s “golden bullet”?

The INKOTA report focuses on Africa, described as the “last frontier” for the fertiliser industry because of its relatively low average use of fertilisers. Only here can the companies hope to grow their market and extract more wealth. Over the past two decades, governments and philanthropic projects, most notably the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA), have worked hand in hand with the global fertiliser industry to subsidise and boost the use of fertilisers on the continent as a way to increase yields. The head of the African Development Bank, Akinwumi Adesina, once described fertilisers as not a silver bullet but a “golden bullet” for African agriculture.

There is, however, growing evidence that these programmes have failed to meet their basic objective of increasing yields and farmers’ incomes, while causing numerous negative impacts. Equally troubling, these programmes have gobbled up large shares of Africa’s scarce public budgets and development aid. Faced with today’s surging fertiliser prices, African governments are simply unable to maintain their subsidy programmes – and African farmers are cutting back on fertilisers, if they are lucky enough to access any at all.

As INKOTA notes: “It is impossible to predict the short to long-term consequences for small-scale food producers who have recently adopted intensive production methods and are now reliant on synthetic fertilisers and long supply chains instead of local nutrient cycles to secure their livelihoods. In all likelihood, the sharp rise in prices, along with a general reluctance on the part of the fertiliser industry to supply markets with low purchasing power, will force farmers to massively cut their use of fertilisers.”

A big decline in food production is on the way in Africa, and this is going to dramatically exacerbate the food crisis already affecting much of the continent.

The only way out of this situation is to put an end to the programmes and policies that promote chemical fertilisers, like AGRA, and to invest massively in alternatives. Fortunately, millions of farmers in Africa and elsewhere have retained the knowledge and the capacity to make this work. They just need the proper support to put that knowledge into practice.

⇢ INKOTA’s report, "Golden bullet or bad bet? New dependencies on synthetic fertilisers and their impacts on the African continent", is available here: https://webshop.inkota.de/node/1691

1 Profits (EBITDA) for Nutrien, Yara and Mosaic: 6M 2022: US$13.9B; FY 2021: US$12.6B; FY 2020: US$6.4B. Data from S&P Capital IQ and 2022 company filings.