Behind the vast yellow maize hills spreading out onto the horizon of Son La province lies tragedy for tens of thousands of small farmers.

Spicier than chilli

The storm had turned the ten-kilometre earthen trail from the centre of Phieng Pan commune to the Xinh Mun ethnic minority village in Na Nhung commune in northwestern Vietnam into a nightmare: fallen trees, rocks and mud covered the narrow path. In some sections, the path nearly disappeared making it treacherous to walk without sustained concentration. After a long journey, I arrived at the home of village leader Mr Lo Van Thu as the sun began to set.

I had arrived well past dinnertime and there were no stores where I could buy food. Looking anxious, my host asked me: "Would you eat sticky rice?" I nodded. Thu’s wife immediately took out some sticky rice that she had made that morning from a bamboo basket, and went out to the garden to harvest a gourd.

She prepared a soup using the gourd and some buffalo bones that hung above the stove in the kitchen. They told me the buffalo had been her only dowry, but it had died after falling down the mountain and getting buried in mud. When they dug it out, it was already dead so they had no choice but to slaughter it. Part of the buffalo was sold on credit to other villagers at a very low price, and the remainder was hung over the stove for their daily consumption.

The couple’s story moved me to tears. Losing the buffalo meant a loss equivalent to VND 20 million, or nearly 900 US dollars.

According to the 2009 census, 23,278 people belong to the Puoc-speaking Xinh Mun ethnic minority group, most of whom live in the provinces of Son La (population 21,288), Dien Bien (1,926), Dong Nai (10), Nam Dinh (10) and Hanoi (10). In Thu’s village, 106 of the 146 households live in poverty. (In fact, the number of poor households may be higher since some may have missed the village meeting where local authorities determined that number—a meeting announced only by word of mouth.)

The livelihoods of Xinh Mun people depend primarily on planting upland rice and on hunting. They practice traditions such as dying their teeth black, chewing betel nut, drinking wine and eating a large amount of spices. And since hybrid maize has been introduced to Xinh Mun villages, they have begun to experience something spicier than chili and more bitter than wine: debt.

Historically, the Xinh Mun people lived a self-sufficient life based on upland rice farming—a life of poverty to be sure, but one free of debt. Then, ten years ago, hybrid maize came to the village along with a number of investors: Mr Ha from Co Noi and Mr Tuan Den (Black Tuan) from Hat Lot were the first investors to come to the village, followed by Mr Bien, Mr Bo, Mr Hung Thu, Mr Dong, Mr Xi Bai and others.

The investors persuaded villagers to stop planting rice and to plant maize instead. They provided them with everything from seeds and fertiliser to rice, salt, MSG, yarn and soup. Everything was made available to the farmers—as long as they signed the debt notes. Since many of them were illiterate, they rarely knew what the notes contained. They just signed or applied their inked finger.

The price of debt

The market price of maize seed is only VND 70,000/kg (US$3.14). However, since investors offer the seed on credit, to be repaid after the harvest, they end up costing upwards of VND 130,000/kg (US$5.83). If farmers don’t pay in time, the price increases to VND 180,000 –200,000/kg (US$8.07-8.97).

While the market price for maize is VND 4,000/kg (US$0.18), the farmers are forced to sell to traders at a much cheaper price (VND 2,500 – 3,000/kg or US$0.11 – 0.13) due to agreements made with the investors. Similarly, the market price for fertiliser is only VND 9,000/kg (US$0.40) but, buying on credit, it ends up costing them VND 16,000/kg (US$0.72) at the end of the season.

From March until June, the farmers have to eat rice supplied by the investors because their spring rice crop will not be ready to harvest until July. The rice provided by the investors is of a very poor quality, unfit for direct consumption and only good for making wine. This low quality rice is sold for VND 10,000 – 11,000/kg (US$0.45 – 0.49) in the market, but they are forced to buy it on credit for VND 20,000/kg (US$0.90).

Traders offer loans to villagers at an average interest rate of three per cent per month or 36 per cent per year. If money is urgently needed due to an illness, wedding or funeral, loans are offered at a 50 per cent interest rate regardless of when the debt is repaid (but not to exceed ten months).

When I met with him, Mr Thu owed VND 20 million (US$896) for buying fertiliser and seeds. If he sells his maize crop to a third party in order to pay this debt, he will be charged an interest rate of 2.5 per cent by the investor. If he sells his crop to the investor, his debt will be deducted from the sale. So his debt of VND 20 million increases to VND 25 million (US$1,121) if he choses to sell his crop to someone other than the investor.

As a result, nearly 100 per cent of the village households are in debt, and 30 – 40 per cent of households have lost land to debt repayment. No one in the village has escaped from debt.

Mr Vi Van Xon used to own three ha of land, all of which he has lost, giving it over to an investor, Mr Xi Bai, for ten years. In addition, he owes an additional VND 40 million (US$1,793). After 17 years of working hard to grow maize, he now has nothing, not even a motorbike. The more he works, the more money he owes. From being the owner of his own land, he has been transformed into a worker on that land. There is no end in sight to his debt, especially as the price of maize continues dropping.

The house of Mr Thu’s father-in-law, Mr Lo Van Phuong, is located at the top of a hill that is entirely planted with maize. In order to plant the entire hillside (nearly 5 ha), he typically needs 60 – 70 kg of maize seeds. But now, all this land belongs to someone else.

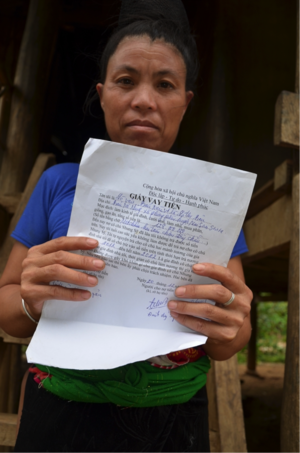

Like many others, Mr Phuong is illiterate. Therefore, he had no way of knowing if the numbers recorded in the debt book were correct. On the date of the land transfer, the investor brought over a red ink pad and asked him to put his finger on it and stamp a piece of paper—a debt receipt. To date, his total debt amounts to VND 165 million (US$7,397).

Mr Thu and the village leader told me that 30 households in Na Nhung had lost their land. Upon signing away their lands, the farmers were overcome with sadness, especially the women, many of them overcome with tears.

In some cases, households signed away their land without the presence of the local authority as a witness. Ms Lo Thi Pan’s family, for example, started planting maize in 2002 based on an agreement with the investor Mr. Dinh Duy Si. She was then supplied with seeds, fertiliser, rice, etc. At first, her debt was as small, but after each season her debt grew—now it is as large as her entire maize field, valued at VND 145 million (US$6,500).

Even after selling off everything in her home, Ms Pan could only pay VND 21 million of her debt. Her husband had to leave home due to this huge debt burden, which was also placed on her son’s shoulders. Her son, Mr Lo Van Thien, had just gotten married that year. He and his wife were forced to work tirelessly from early morning to late in the evening every day in order to pay the debt.

Finally, their efforts paid off when they harvested an abundant crop of large-sized maize. They sold the crop for VND 52 million, all of which went into the pocket of the investor, who then forced them to sign another debt note to give over their land from 2012 to 2022. If they didn’t sign, the investor threatened to report them to the authorities.

Terrified by the threat, Mr Thien and his mother immediately signed the debt note giving three ha of land (for sowing 60 kg of maize seeds) to the investor. Instead of containing money, his safe is now filled with debt receipts.

Adapted by GRAIN. The original article, in Vietnamese, is available at: http://m.nongnghiep.vn/nuoc-mat-noi-buon-va-bi-kich-cua-ngan-van-kiep-nguoi-trong-ngo-o-son-la-post174288.html