Communities lose out to oil palm plantations | A long history and vast biodiversity

The Americas

The Americas

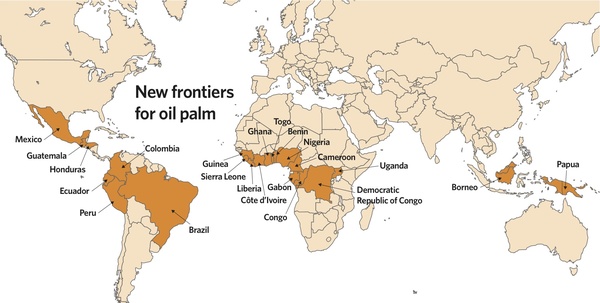

Palm oil is not something you would associate with a Mexican kitchen. But go to any supermarket in the country, and you will find countless products containing it. The country's food system has changed immensely since the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) came into effect in 1994 and multinational companies moved in to take control of the country's food supply. The alarming rate of obesity, now higher than that of the US, is one manifestation of Mexico's changing food landscape, and tied to this is the escalating consumption of palm oil.

Palm oil consumption has increased by over four times since NAFTA was signed, and it now accounts for one quarter of the vegetable oil consumed by the average Mexican, up from 10% in 1996. Other countries in Latin America undergoing similar changes to their food systems have also increased their consumption of palm oil. Venezuelans have doubled their intake, and Brazilians are consuming 5 times what they did in 1996.

This growing consumption is matched by growing production, not in Mexico, but in those countries where oil palm can be most cheaply produced. A third of Latin America's palm oil exports now go to Mexico.

Colombia, with about 450,000 ha under production, is the biggest palm oil producer in the Americas. Since the late 1990s, Colombia's palm oil production has taken off for several overlapping reasons, including government incentives and a national biodiesel mandate. Oil palm has also been promoted as a substitute crop for coca as part of the US-backed "Plan Colombia" – a programme aimed at ending the country's long-standing armed conflict and curbing cocaine production. Paradoxically, palm oil is also proving a useful way for drug cartels, paramilitaries and landlords to launder money and maintain control of the countryside.

Disease outbreaks have limited palm oil's expansion in Chocó Province and most of the expansion has instead happened on the pasture lands of the central and eastern parts of the country, where the oil palm industry claims there is little deforestation and displacement of peasants. But studies show that these pasture lands are in fact typically common areas vital to peasants for the production of their food crops and the grazing of their livestock. The "pasture lands" are often the only lands that peasants have access to, and palm oil companies routinely use force and coercion, including paramilitaries, to take control of these lands from them or to force them into oppressive contract production arrangements. Across Colombia, the expansion of palm oil and the presence of paramilitaries are tightly correlated.

Ecuador, Latin America's second largest palm oil producer, has also seen a recent expansion in oil palm production. While much of its palm oil is produced on farms of less than 50 ha, new expansion is driven by private companies who have been moving into the territories of Afro-Ecuadorians and other indigenous peoples in the Northern part of the country, leading to severe deforestation and displacement and meeting with stiff local resistance.

Land conflicts over palm oil are also erupting in Central America. In Honduras, peasants in the Aguan Valley have been killed, jailed and terrorized for trying to defend their lands and small palm oil farms from powerful national businessmen who have been grabbing their lands to expand their palm oil plantations with the backing of foreign capital. Ironically, these peasant families first moved into the forests of the Aguan in the 1970s as part of a government land reform programme, and were encouraged to grow palm oil and establish their own cooperatives. The neoliberal policies of the 1990s and a coup d'état in 2009, opened the door for powerful local businessmen like Miguel Facussé, to destroy the peasant cooperatives, violently grab lands for plantations, and reorient the supply chain towards exports for biofuels and multinational food companies. Likewise in Guatemala, where production of palm oil has quadrupled over the past decade, the palm oil sector is now entirely controlled by just eight wealthy families who have been aggressively seizing lands from indigenous communities, such as the Q'eqchi,

Some industry insiders predict that an expansion of oil palm production in Brazil will soon dwarf all other production in the region. Brazil is a net importer, and production has so far been confined to a small area of Pará, in the North. But, unlike in other regional palm oil producing countries where production is dominated by national companies and wealthy landowning families, transnational corporations have recently made significant investments in Brazilian palm oil production, such as the mining company Vale, energy companies Petrobras and Galp, and ADM, one of the world's largest grain traders and a major shareholder in the world's largest palm oil processor Wilmar.

Going further

Tanya M. Kerssen, "Grabbing Power: The New Struggles for Land, Food and Democracy in Northern Honduras," FoodFirst, 1 February 2013

Human Rights Everywhere, “The flow of palm oil Colombia- Belgium/Europe: A study from a human rights perspective,” 2006

Papua (Papua Province – Indonesia, West Papua Province – Indonesia, Papua New Guinea)

Papua has a long, sordid history of resource extraction by mining and forestry companies. But only recently has there been much corporate interest in the area's agriculture, and it's difficult to judge how genuine this interest is. Many of the large land deals for palm oil have been acquired by forestry companies that are mainly interested in logging out the trees. Once the trees are gone, the companies are likely to close up shop and move elsewhere.

The situation in Papua is not so different from what has transpired in other parts of the world where oil palm plantations have been established. Oil palm expansion tends to follow the path of logging. The forestry companies that logged out the rain forests of Borneo, like Sinar Mas and Rimbunan Hijau, became major players in the palm oil sector and they are now turning to Papua's forests with the same model, as are a new batch of companies that are more focused on oil palm, such as Wilmar, the Siva Group and Far East Holdings Berhad. Added up, palm oil companies have acquired over 2 million ha for plantations across the Papua area.

Papua's governments are active players in helping these companies to secure lands and override local opposition. Politicians in Papua New Guinea are often financially involved in the deals with oil palm companies, and rarely is consent sought or given from the affected communities where the land leases are taken. In 2011, public protest forced the government to establish a commission of inquiry to investigate the awarding of land leases. In its report to parliament in September 2013, the commission said the land lease system was "marred by shocking corruption and mismanagement". Of the 42 leases it examined, only four had secured consent from local landowners and had viable agricultural projects.

The Indonesian government has been steamrolling ahead with a massive, 2.5 million ha plantations project called the Merauke Integrated Food and Energy Estate (MIFEE) in the territories of indigenous Malind communities within Western Papua Province. In July 2013, a coalition of 27 organisations made a submission to the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Commission urging it to take urgent action to protect the Malind from the MIFEE. The submission relates how the Indonesian government and foreign and national companies are working together to lure Malind communities into ceding vast extents of their lands for agricultural plantations, particularly for oil palm and sugarcane.

"Consent, where sought, is obtained through coercion, deceit, misinformation and the purposeful manipulation and fragmentation of the Malind’s customary community collective decision-making processes and representative institutions," says the submission. "Terms of compensation are unilaterally imposed rather than negotiated, at rates of less than 0.86 USD per hectare per year per clan. Without exception, interactions between the company and the communities are held in the constant presence of the military and armed forces, such that freedom of expression is restricted and objections to the proposed developments stifled."

An estimated 2 to 4 million workers are expected to migrate to the area because of the project, "overwhelming and further threatening the rights and well-being of the Malind who number approximately 52,000 persons."

Already, 33 land permits have been given to companies for oil palm plantations under MIFEE. Just four companies have 25 of these permits, covering an area of 948,500 ha.

Going further

Oakland Institute, "On our land: Modern land grabs reversing independence in Papua New Guinea," November 2013

AGRA and PANAP, "Land Grabbing for Food and Biofuel (MIFEE Case Study)," 2012

Longgena Ginting and Oliver Pye, "Resisting Agribusiness Development: The Merauke Integrated Food and Energy Estate in West Papua, Indonesia," April 2011

Borneo (Kalimantan - Indonesia, Sabah - Malaysia, Sarawak - Malaysia)

More land has been grabbed for oil palm on the tropical island of Borneo over the past decade than anywhere else on earth. Between 2000 and 2009, the area under oil palm plantations in Borneo more than doubled, from 2.4 million ha to 5.4 million hectares.

Sabah and parts of Kalimantan had already experienced major waves of oil palm expansion. In the 1980s and 1990s, palm oil companies from peninsular Malaysia were allocated huge areas of degraded forest lands by the Sabah government, while in Kalimantan, starting in the 1970s, the Suharto regime sent millions of families from other densely populated parts of Indonesia to clear forest lands and cultivate oil palm in the territories of indigenous peoples under a national land distribution programme.

The current second wave of oil palm expansion in Borneo continues to target the customary lands of indigenous peoples, who account for about 40% of the island's population. In 2012, there were 108 documented land conflicts between local communities and palm oil companies in Kalimantan alone, with more than 90% of them involving indigenous communities.

Multinational palm oil companies have been deeply involved in the expansion of oil palm in Sarawak and other parts of Borneo. Sime Darby has over 100,000 ha planted with oil palm in Sabah and Sarawak and 45 of the 71 plantations it operates in Indonesia are in Kalimantan. Wilmar, the world's largest palm oil processor, has over 160,000 ha of plantations scattered across the island. Even the Tabung Haji, which manages the savings of Malaysians for the pilgrimage to Makkah, owns 24 plantations in Sarawak and Sabah through its subsidiary TH Plantations, as well as 42,000 ha in East and Central Kalimantan through a joint venture with Felda Global, the world's third largest owner of oil palm planter. TH Plantations has been embroiled in several land conflicts with indigenous peoples in Sarawak, including a conflict in Simunjan with an Iban community that, after getting nowhere with peaceful efforts to stop the company from encroaching on their lands, torched 16 of the companies' tractors.

Some of the largest oil palm plantation operators in Borneo are logging companies that diversified into palm oil in the late 1990s after clearing out much of the island's more lucrative forest areas. These companies are able to convert the extensive forest permits they have acquired into oil palm plantations or flip the lands to other palm oil companies. Friends of the Earth estimates that logging companies in Sarawak, for example, have acquired around 280,000 ha of lands for oil palm plantations by way of Planted Forest licenses. A number of Sarawak's largest logging companies, such as Samling and Rimbunan Hijau, are now setting up plantations globally in the Indonesian Borneo, Papua and even Africa.

Several major state-backed projects are also in the works that would bring corporate investment in plantations to parts of the Borneo that have not yet been touched by oil palm expansion. The biggest state project is the Kalimantan Border Oil Palm Mega Project, which would involve eighteen, 100,000 ha plantations near the Malaysian border.

Going further

Down to Earth Indonesia website

Global Witness, "Inside Malaysia's shadow state (Film)", 2013

Friends of the Earth Europe, "Commodity Crimes: Illicit land grabs, illegal palm oil, and endangered orangutans," November 2013

Forest Peoples Programme, Sawit Watch and TUK Indonesia, "Conflict or Consent? The oil palm sector at a crossroads," 2013

Communities lose out to oil palm plantations | A long history and vast biodiversity