New frontiers for oil palm | Oil palm production in West and Central Africa

Africa: another side of palm oil

There is a part of the world where palm oil is not synonymous with deforestation and plantations, where it is not an export commodity but an essential ingredient in local dishes, and where its production profits peasants not bankers. In Africa, the centre of origin for oil palm, tens of millions of people, most of them women, rely on this tree for food and livelihoods.

The global land grab for plantations puts these people, the oil palms they look after and their traditional systems of production at tremendous risk. Resistance, for them, is not just a matter of holding onto their lands and forests. It is also a fight for their livelihoods, their cultures, their biodiversity and their food sovereignty.

A long history and vast biodiversity

From the plantations of Malaysia to the small farms of Honduras, all oil palms trace their origins to Africa. It was here, long ago, somewhere in the western and central parts of the continent that people first began to use the plant for their needs. They discovered dozens of uses for the plant, and it soon became an integral part of their food systems and local economies and cultures. In the traditional songs of many countries of West and Central Africa, oil palm is called the "tree of life".1

Béninois song: translated into English

Mi kpon détin nin dji aga

Look at the top of this palm tree

Ogbè é do détin nin dji aga don

Look at the life at the top there

Mikpon détin dji aga, mi kpon mi kpon détin nin dji aga don

Look at the top of this palm tree, please look at itO ho é do han tché nin min

What you can take from my song

Wè gnin do détin nin é do téé

Is this: that the palm tree standing there;

Min dé djro gbè toin nan dou donan lébé nan bo nan non sin

Anyone who wishes to benefit from it should care for it and worship it

Mikpon déman é ton édo non bolo akiza

Look at its leaves which are used for making brooms

Mikpon dékpa nin sin do wè é do non bolo do toh kan

Look at the parts which are used for making ropes to draw water from the well

Détin é ka do té a nan mon dékpa bo mon délian

From the palm tree, you get branches and cakes

Détin do kpo nin dji wè dé sounhlouin gan gan soun gan dé

On the same palm tree there are big stems which hold nutsMi kpon ami é ton, a nan mon ami dja kpo atan kpo

Look at the liquids it produces: palm oil and wine

Mindé djro gbè ton nan dou,

Anyone who wants to benefit,

dékin min wè tchotcho akou non ton son

should know that we get the best quality oil from these nuts;Mi kpon détin nin dji aga

Contemplez le sommet de ce palmier à huile

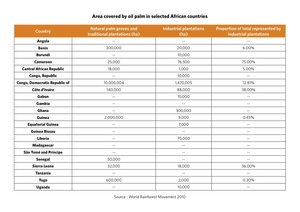

In Africa, oil palms on plantations make up only a small percentage of the total. Most oil palms are still grown in the groves in mixed forests. These groves are often cared for and harvested by particular families, passed down from generation to generation. Such semi-wild groves are found in large parts of Africa, from Senegal in the west, to the southern end of Angola, from along the banks of Lake Kivu and Tanganyika on the East African coastline, and even on the west coast of Madagascar. Nigeria contains the continent's largest area of wild or semi-wild palm groves, with over 2.5 million hectares.

Oil palms are also grown on small farms on the continent. African farmers in West and Central Africa mix oil palms with other crops like bananas, cacao, coffee, groundnuts and cucumbers.

The type of oil palms grown in Africa are also significantly different from those grown elsewhere. Most palm oil in Africa is produced from the traditional dura variety, which grows in the wild, and not the high yielding crossbreeds used on plantations in Africa and elsewhere. Even though the dura variety produces less yield compared with modern varieties, many African peasants prefer it because it creates less shade and therefore does not hinder the growth of other crops on their farms. They also favour it for the quality of palm oil it produces, which sells for a premium in local markets.

Natural reproduction

In Côte d’Ivoire, the survival and reproduction of this plant depend on a small animal, a squirrel known in the Yacouba language as “gbe”. The squirrel lives in the trees and eats the ripe palm fruits and spreads its seeds with its droppings; indeed, its behaviour is a reliable indicator of when the fruits are ripe.. Birds are also part of the oil palm's reproductive cycle, carrying the fruits and hence the seeds far away from the parent plant. Some farmers in the central region of Cameroon transplant palm seedlings out of the forests onto small plantations ranging up to just over two hectares.

Palm nuts dropped on the ground by people, mammals, and birds sprout everywhere. In addition, the process of harvesting the clusters and removing the nuts in the forest causes many seeds to fall on the ground, helping to renew the palm groves and encourage the trees to grow around villages.

In the local markets of West and Central Africa, the quality of a palm oil is typically judged by its colour. African women say that the palm oil extracted from traditional oil palms is better because it is more red than that extracted from the modern varieties. In Benin, traditional palm oil sells for 20-40% more in the markets than that from modern varieties.2 African women also say that their traditional sauces made with boiled palm kernels have a lighter and thus better texture when made with kernels from traditional palms than with those from modern ones.

A love affair with traditional palm oil in Côte d'Ivoire

Palm oil has long been the vegetable oil of choice in Côte d'Ivoire. The average Ivorian consumes about 10 kilos of it per year. It is used not only for frying but also as a main ingredient for many local dishes, from gombos and other sauces to various dishes made with plantains or foufou. Palm oil gives these foods a particular taste and colour that is highly valued in Ivorian cuisine.

Imports and highly refined palm oil from industrial plantations and modern mills have taken a share of this market from traditional producers. But despite higher prices, consumers remain loyal to traditional palm oil, even in the cities.

The study found that Abidjan's discerning consumers prefer palm oil derived from wild or semi-wild oil palms (so-called “African” oil) over palm oil derived from modern high-yielding varieties (referred to as “sodepalm” for the former agroindustrial oil palm corporation). They also differentiate among the territories where palm oil is produced, such as Bouaké, Gagnoa, Bouaflé, Adjukru, or Attiés, with preference given to those regions where modern varieties are not cultivated.

According to the study, the highly prized “African” oil, which cooks consider to be the “genuine article,” fetches twice the price of inferior-tasting “sodepalm” oil (490 CFA francs for sodepalm oil versus 915 for African oil).

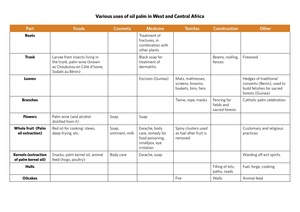

But traditional oil palms offer much more than a high quality palm oil and kernel. Unlike on industrial oil palm plantations, African communities use every part of a traditional oil palm, from its roots to its branches to produce everything from wines and soups, to soaps and ointments, traditional medicines and animal feeds, and even a whole range of textiles and housing materials.

Palm wine in the Congo

In the Congo, wine made from oil palms has various uses.

Palm wine is mixed with certain leaves is used to treat fractures and palsies.

Palm wine mixed with other products is used to treat endemic diseases.

Palm wine spiced with a very hot local pepper variety is an effective cold and flu remedy.

Palm wine is used to treat snakebite and to alleviate breastfeeding-related difficulties in lactating women.

(by CEPECO Congo)

Traditional medicines from oil palms in Cameroon

(by Marie-Crescence Ngobo, RADD)

All parts of the oil palm, including its byproducts, are raw materials for making indigenous remedies. The Yambassa people in Mbam use the leaves of traditional oil palms to treat tooth decay. Palm wine mixed with various other ingredients is used as a remedy for male impotence, chlamydia, gonococcal infections, stomach ache, jaundice, and measles.

The Mvele, a Beti sub-tribe, prepare a meal of hearts of oil palm for new mothers, as it stimulates milk flow.

Black palm kernel oil, which the Bantu call manyanga, has a range of cosmetic and medicinal applications. It is used in skin and hair care and is an indispensable and ubiquitous ingredient in formulas for newborns. All modern maternity wards strongly recommend it in place of other baby formulas. It has been shown that children rubbed with manyanga are less susceptible to disease. In former times, the Beti used a mixture with other ingredients as a pigmentation agent for children born lighter-skinned, who were more likely to become sickly.

Palm kernel oil also lowers fever in children. Mixed with other ingredients, it is a good remedy for stomach ache and is also administered for malaria, cough, and earache.

The roots can be chewed on to relieve a toothache. They are also a good nasal decongestant.

The burned husk is an antiseptic and an antibacterial. For a persistent stomach ache, consumption of powdered coal from the traditional palm nut is advised. Coal made from the kernel also serves as a teeth whitener and communities in southern Cameroon use it as a toothpaste. Ash from the burned tree bark relieves boils.

Ash from the leaves of teis boiled for many hours until the water is gone. A valuable type of salt is produced by burning the tree's branches, then dissolving the ash in water and boiling the solution for hours. The resulting powder was used for cooking before being supplanted by salt from other sources. Women with babies and young children should always keep a supply of this salt on hand, as it is an ingredient in traditional remedies for conditions affecting children.

Oil palm fronds are also used to treat sprains.

New frontiers for oil palm | Oil palm production in West and Central Africa

Notes

1 The following is based in part on field studies that were carried out by GRAIN in 2013 in collaboration with Réseau des Acteurs du Développement Durable (RADD) in Cameroun, INADES – Formation (Institut Africain pour le Développement Economique et Social) in Côte d’Ivoire, ONG ADAPE (Association pour le Développement Durable et la Protection de l’Environnement) in Guinea and CEPECO (Centre pour la Promotion et l’Education des Communautés de base) in the Congo.

2 Stéphane Fournier, André Okouniola-Biaou, Isaac Adje, "Importance of 'local' commodities: palm oil production in Benin", Oléagineux, Corps Gras, Lipides, Volume 8, Number 6, 646-53, November - December 2001

3 Emmanuelle Cheyns, "La consommation urbaine de l'huile de palme rouge en Côte d'Ivoire : quels marchés ?" Oléagineux, Corps Gras, Lipides, Volume 8, Numéro 6, 641-5, November-December 2001