A long history and vast biodiversity | Well oiled resistance

Oil palm in Basse-Guinée and Guinée Forestière

(by Alphonse Yombouno, ADAPE-Guinée)

The oil palm is has long been valued for its versatility. All parts of the plant, from the roots to the flowers to the by-products, are used for food, traditional medicine, and for their important sociocultural value.

Palm groves and oil processing, along with the other services related to palm production, have historically contributed to the development of our local economies and still do today, since these products are used in our communities for food (palm oil, wine and alcohol) and traditional medicine (soaps made from palm and palm kernel oils, ointments derived from palm kernel oil).

Throughout the regions of Guinée Forestière and Basse-Guinée, small-scale palm oil extraction is a very important economic activity for nearly all families and peasant farms. The industry employs not only growers but also processors and merchants.

The red oil is used as a remedy for food poisoning and smallpox, while palm kernel oil is used to treat earache.

Some communities in the two regions prefer to harvest natural stands of oil palms in the forest instead of planting palm groves. However, large corporate plantations, individual growers, and research centres use trees imported from Côte d’Ivoire.

There are mills in each region for processing the kernels into palm kernel oil, offering an income-generating opportunity for producers in rural communities and a source of soap for consumers.

In addition to oil, the main products extracted from the palms are fibre from the leaves and a beverage, known as bandji in the Maninka language or touguiyé in Susu, from the sap.

Naturally brewed palm wine is sold in small containers or bottles along roads and in hotels and bars throughout Guinea. This traditional beverage is often used in celebrations (weddings, customary or religious rites), most notably in sacred groves in forested regions.

Fibres and kernels left over from oil extraction are dried in the sun to be used as fuel for the future batches of palm oil. The ash from the process is spread on fields as fertiliser.

The oilcakes (fibre and nut chaff) produced as a byproduct of the process are used as feed for cattle, pigs, and poultry.

Processing techniques for oil palm products (palm oil, palm kernel oil, palm wine, and distilled palm alcohol) are a common feature of the history and traditions of these regions.

History of oil palm use in the Bas-Fleuve District, DRC

(by Pastor Jacques Bakulu, CEPECO)

Even before colonisation, our ancestors knew and valued oil palms as a food, as well as in economic and social terms. The plant was a boon to them as they drank its wine, cooked with its oil, used its branches as building materials, and so on.

Our ancestors would pile the ripe palm fruits in holes dug for the purpose1 and allow them to ferment. The fruits were left for a considerable time before being mashed in a mortar, producing a thick paste.2 While in West Africa (Benin, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea), small-scale palm oil extraction is done by the grower or buyer of the “raw” fruits or clusters, in the Congo this is not the case. Here, the paste was cut into blocks, packed, and then sold or traded to the colonists or to neighbouring countries, where the palm oil itself was extracted. This activity was an important source of subsistence income for many families, and the wealth of a clan or family could be gauged by their ability to process palms in this way.

Even today, the holes dug to ferment ripe palm fruits constitute historical evidence of the existence of each village, or even each clan, in the Bas-Fleuve region.

The existence or ethnic affiliation of a village lacking a “mabulu ma zieta” is subject to challenge on the grounds that the ancestor was incompetent or never existed in the first place. Thus, oil palm is bound up with the history of populations existing today in our area of activity.

The economic importance of oil palms to Africa is huge, particularly when it comes to women. They handle most of the production, from the harvest and processing of palm oil, to the sale of the oil and other oil palm products in the local markets. The income they earn makes a critical contribution to their households. In the south of Benin, for example, around a quarter of all women earn some part of their income from the processing and sale of palm oil.3

“In Guinea, the oil palm sector is still today a source of stable employment, and as such helps to stem the rural exodus and to develop the local economic fabric. It plays an important subsistence role for peasant families thanks to the many business opportunities it provides and the multiple uses it has in the traditional economy,” says Alphonse Yombouno of ADAPE-Guinée. “Every able-bodied individual is put to work during the production, processing, and marketing of these products.”

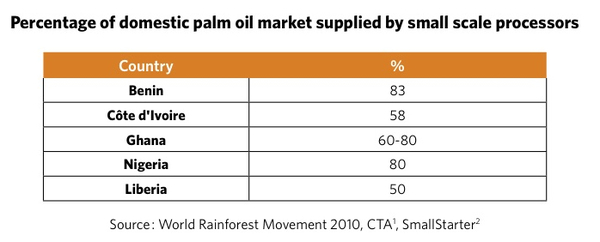

This informal sector, managed mainly by rural women, continues to supply Africa with most of its palm oil, the vegetable oil of choice for much of Africa, despite the competition from industrial plantations. The table below shows how small scale producers account for most of the market in some of the African countries that consume the most palm oil.

The reality, however, is that a growing amount of palm oil is being imported into African countries, oil which could easily be supplied by small scale producers if the proper policies were in place. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), for instance, where small-scale producers produce nearly 90% of the country's domestic palm oil production, imports have grown to account for 81% of the domestic market. If those imports were curtailed and the domestic sector was protected from foreign oil palm companies, it would open up a tremendous economic opportunity for rural women in the DRC.

Oil palms in Benin: The inconvenient truth

Oil palms in Benin: The inconvenient truth

(by Hubert-Didier Madafimè, journalist, Radio National)

Oil palm was Benin’s first export industry, before undergoing a decline in the early 1970s despite significant advances in scientific research. Oil exports have declined sharply since then and only 40% of domestic vegetable oil requirements are now covered by domestic production (280.000 tonnes in 2005). This was the situation when President Thomas Yayi Boni took power in 2006. Boni had stated that the oil palm sector would be revitalised along the same lines as the cotton sector. He announced this at the beginning of his first term, in conjunction with an investment of 14 billion CFA francs in cotton. But Boni either did not know or was not told that the oil palm sector in Benin faces problems linked to growing conditions that will make it hard to boost production.

It was this fact that led Boni to retain the services of a Malaysian oil palm expert in an attempt to put his announced intention to revitalize the sector into effect. It was only after the expert had arrived in the country that the government realised it did not have enough land available for the projects being proposed. Then began a race against the clock to persuade people to sell or lease their land for oil palm production – a race that ended in failure. In Lokossa they were chased out by machete-wielding locals who remembered an earlier episode, in 1966, when the government had expropriated local landowners for an oil palm project at Houin-Agamey, one whose negative effects are still being felt today. The government quickly realised that there was no vacant or even fallow land available: it was all owned by families or communities, and there was no way to wrest it away from them. A few months later the expert left Benin with nothing having been accomplished. He was rumoured to have stated before leaving that "Conditions in Benin are not suited to the growing of oil palms.”

Yet Benin was, in the 1960s, the subregion’s leading producer of palm oil. With the departure of the Malaysian expert, the announced reforms could not be put into effect. Since the withdrawal of government support, a number of cooperatives (Houin-Agamey, Hinvi, Grand Agonvy) have been plagued by problems related to abuse of trust and suspected mismanagement, and the whole sector has suffered as a result. Today, one is tempted to state that the Beninois oil palm sector has practically ceased to exist.

The oil palm sector in Côte d'Ivoire

(by Kadidja Kone, INADES-Formation (Côte d'Ivoire)

A participatory survey of practices for the processing of traditional oil palm byproducts, involving interviews and field observation, was conducted in Dakouépleu and Douèleu, two Yacouba villages in the Logoualé sub-prefecture (Department of Man, western Côte d’Ivoire). In this region, oil palms are grown and harvested in the wild.

The respondents stated that the oil palm is a gift from nature; that their ancestors were born from God and found that the oil palm had been given to them. For the Gouro people of west and central Côte d’Ivoire, “The oil palm is what Bali, God the creator, gave human beings before putting them on the earth. He gave it to them for food. Human beings and palm trees are one and the same: we are both here on the earth. It watches over us, as God intended. That is why this tree never dies; even under the hottest sun, even in the dry season, it stays green.” In terms of symbolism, the palm is the emblem of beauty and goodness; with the feeling of fresh humidity it gives off, it is seen as calm, gentle, and peaceful.

Plans to expand oil palm production in Africa are having negative impacts on the means of subsistence of local populations, both for those affected by existing plantations or people living in regions targeted for new ones. Most of the African countries to which the oil palm is native are being pushed by their governments and by foreign financial institutions into a production model that causes problems for local populations. Millions of hectares have already been set aside for palm oil-based agrofuel production, with the result that whole communities are being pushed off their land. They are losing their livelihoods and watching their biodiverse natural ecosystems give way to palm monocultures. Women in particular are losing a valuable source of income offered by palm oil.

In Côte d’Ivoire, industrial corporations (Palm Côte d’Ivoire, Palmafrique, Société Internationale de Plantations et de Finance en Côte d’Ivoire (Sipefci) have occupied some 250,000 hectares with palm plantations.4 Alongside the modern plantations, natural or wild palm groves still exist, especially in the south and central portions of the country, the gallery forests of the northern savannas, and the montane area of Man. Unrefined red oil, prized throughout the country, is produced in artisanal fashion from these trees.

The red oil is an ingredient in stews such as wild spinach stew (sauce feuille) and dried or fresh gumbo stew (sauce djumblé, sauce kopé). It is also found in common dishes based on plantains, manioc, or yams: fufu (boiled plantain or yam pounded into a dough), attiéké (fermented manioc) stew, “red” attiéké made from boiled yams, and alloko (fried plantains). Red oil is incorporated into gumbo stews as a condiment, rather than being used to fry meat or fish as refined palm oil would be, presumably because it gives them a distinctive colour and taste. But in wild spinach stews, red oil may be used to fry the fish or meat.5 Thus, each of these oils has a number of specific uses.

Traditional oil palms produce an abundant crop from January to May, with production tailing off in June and July.

Oil pressed from wild palms keeps for 5 to 7 months; the women who use it state that its shelf life can be extended by adding a ripe plantain or some sugar to the oil. The barrel containing the oil is then placed on a pallet. Traditional palms are exploited on a small-scale basis, and the skills for doing so must be learned from elders. The equipment used remains the same as in former times. The women note that a few young men have gotten into palm processing in recent years.

The oil obtained from the nuts is used in cosmetics and to produce a soap considered a remedy for fever and skin conditions (acne, ringworm).

Oil palm roots mixed with other medicinal plants are administered as a remedy for swelling.

The tree's wood can be used to build beds and stools, while strips cut from the palm frond's leaflets are woven into baskets, dryers and hoop nets. They can also be bound together to make brooms.

Whole palm fronds are used for fencing and roofing (houses, showers).

The central spine of the leaves, the rachis, is boiled down into a traditional salt that is rich in potassium and low in sodium. It is recommended for people who are on low-sodium diets.

Local knowledge related to the oil palm constitutes a rich heritage that can and should be capitalised on to safeguard Ivorian and African biodiversity. While the plantations and factories of the industrial system employ relatively few workers – several thousand at best – the traditional system provides products and income for millions of people, women in particular, who are involved in the harvesting, processing, and marketing of palm oil, kernels, and wine.

A long history and vast biodiversity | Well oiled resistance

Notes

1 These holes are known in the Kiyombe dialect as mabulu ma zieta – literally, “mixing hole.” Kiyombe is a spoken by the Yombe tribe, a subgroup of the Kongo, in the Bas-Fleuve District, Province of Bas-Congo (see administrative map of Bas-Congo, above).

2 This paste was called zieta in Kiyombe.

3 Stéphane Fournier, André Okouniola-Biaou, Isaac Adje, "Importance of 'local' commodities: palm oil production in Benin", Oléagineux, Corps Gras, Lipides, Volume 8, Number 6, 646-53, November - December 2001

4 Claudie Haxaire, L’huile de palme chez les Gouro de Côte d’Ivoire in Journal des africanistes. 1992, tome 62 fascicule 1. pp. 55-77.

5 La consommation urbaine de l'huile de palme rouge en Côte d'Ivoire : quels marchés ?, Oléagineux, Corps Gras, Lipides. Volume 8, Numéro 6, 641-5, Novembre - Décembre 2001, Dossier : L'avenir des cultures pérennes